‘I must be famous to be heard’

Esha Niyogi De’s new book reveals a previously hidden narrative about women in South Asian cinema

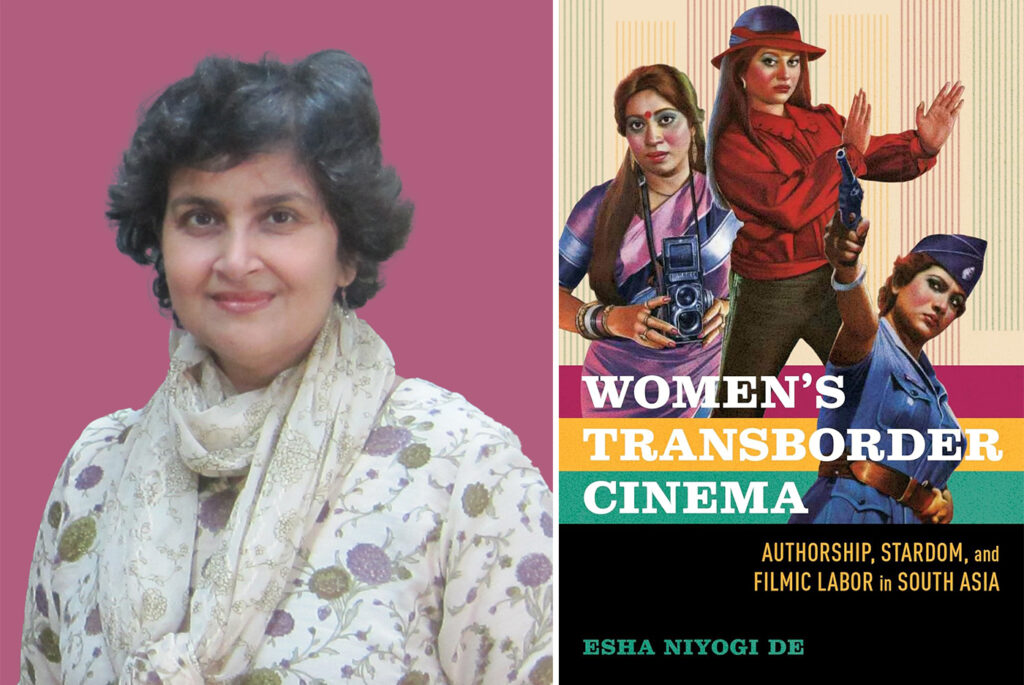

Courtesy of Esha Niyogi De (left); University of Illinois Press

De’s book focuses on “star-authors” — women who produced and starred in their own films — in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India during the latter half of the 20th century.

| April 14, 2025

When Esha Niyogi De traveled to South Asia at the end of 2013 to research women in cinema, she uncovered an unexpected narrative.

De, a senior lecturer in UCLA Writing Programs, was visiting the region with the support of a Fulbright regional research award. The work she began then led to her second monograph, “Women’s Transborder Cinema: Authorship, Stardom, and Filmic Labor in South Asia,” which was published in December by University of Illinois Press.

The book unearths a previously hidden history of “star-authors” — women who produced and starred in their own films — in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India during the latter half of the 20th century. De’s research found that star-authors crossed territorial, conceptual and institutional borders in both the aesthetics and production of their films as a form of resistance.

Here, she discusses how the framing for her book evolved, the surprises and challenges she encountered throughout her research and the importance of the term “transborder” in the book’s title.

How did the subject matter for your book come into focus?

This project began as a comparative one, looking at the new generation of women’s issues-centered filmmakers across the borders of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. But that changed after I spoke with Samina Peerzada, a brilliant actress, film producer, director and TV personality in Pakistan.

What surprised me was her insistence on how important it was for her to be famous to make issues-based films in the industry. She said to me, “I must be famous to be heard.”

After speaking with Samina, as well as fans of 1980s action-heroine cinema who brought me DVDs to watch, I became interested in the female star-authors, and I knew I had to change my project.

Stars turning into filmmakers had not been explored in any great detail in film history or scholarship. I thought there had to be a story here about the importance of star fame in bringing in resources and opening doors for women filmmakers, especially in the smaller markets of Pakistan and Bangladesh, where they had more narrative control.

What were some of the challenges of researching these hidden stories?

Talking to filmmakers and film personnel and gathering oral histories was very important, but it was difficult to penetrate the film industries and find contacts. Fortunately, film journalists and connections I made through Fulbright helped me network and make inroads.

In India and Bangladesh, there are state-supported official film archives. But the challenge was to actually find the women filmmakers. If their contributions were documented, it was because they either won national awards or they were credited as being there to do household-type labor or merely as a tax incentive. The archives also separated the women’s stardom from their production history; typically, if a woman starred in and produced a film, her production work was written out of the history.

In Pakistan, the challenge was that there was no official film archive. Fortunately — and unexpectedly — I found an unofficial archive of pirated video discs floating around the market. The research process was full of these challenges and turning points, but that made it very rewarding.

I take it that you used the term “transborder” in the book’s title to describe more than just the geographic boundaries between the countries you studied.

Yes. I used “transborder” to refer not only to territorial borders but also conceptual and institutional ones.

Gender, for example, was an important conceptual border. Women often portrayed tough action heroines who fought for their families against villainous men trying to destroy them, while the “good” men were all dead, imprisoned or debilitated.

And gender-queering in films was a point of resistance against the gender violence taking place under [Muhammad] Zia-ul-Haq’s regime in Cold War-era Pakistan [from 1978 to 1988]. During the same era, when partitions divided South Asia, women built solidarity across borders to keep connections alive.

There is a history of women star-authors of the 1980s, including Shamim Ara, who traveled from Pakistan to Sri Lanka after the division of Bangladesh and Pakistan. They co-produced films and got them dubbed in the local language to be released in Bangladesh at a time when the states were so antagonistic.

The term “transborder” also allowed me to scrutinize the opportunities of the new generation active in the 2000s. Although there are so many more opportunities for women filmmakers nowadays, borders come in new forms — financial pressure, gender-based gatekeeping or the way production houses’ decisions are driven by marketing considerations. Those borders can be less obvious, but it continues to be a struggle for this generation of women filmmakers.

What does it mean to you to share this work with the world?

It was a privilege to cross these borders, work in the archives and libraries and talk to women star-authors as well as their families, friends and fans. These are postcolonial parts of the world that are so broken up, so they’re hard borders to cross. There was little to no research on collaborations between filmmakers or culture producers in, say, India and Pakistan, or Bangladesh and Pakistan.

So many women talked to me about their challenges and triumphs, their memories and how meaningful these films were and continue to be. In my conversations with fans, women recounted stories of watching these films together and sharing them with each other in spite of the draconian regime in power at the time. That was so eye-opening for me — that women watched these women-made films.

In many ways, this book, with its emphasis on Muslim-majority societies, is a rebuttal to the ideas that Muslim women are being suppressed and that people in those societies don’t care. This is not true. Muslim women are very strong and innovative. They cross borders in their own way.