His career is the ‘story of the African American literary tradition’

On the eve of a symposium in his honor, colleagues pay tribute to Richard Yarborough

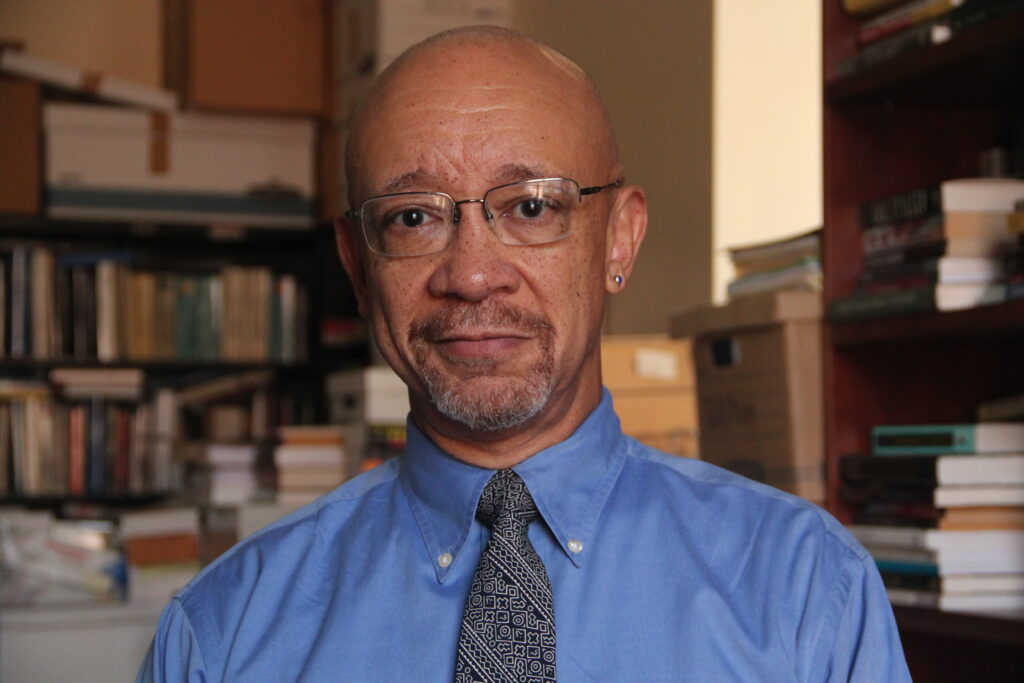

Christelle Snow/UCLA

Richard Yarborough, a UCLA faculty member since 1979, will be celebrated at a symposium in his honor on Dec. 6.

| December 5, 2024

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of Richard Yarborough’s career on the study of African American literature and U.S. literature more broadly, or of his many and diverse contributions to UCLA. But one way to at least contextualize the indelible mark he has made is to consider what colleagues and students say about his scholarship and mentorship, and about the breadth of his expertise and the scope of his achievements.

Yarborough, a professor of English and of African American studies, retired in June after 45 years as a UCLA faculty member. Perhaps not surprisingly, his emeritus status hasn’t kept him from teaching (he’s leading a course on early African American literature this quarter) or continuing to advise graduate students.

On Dec. 6, friends, colleagues and former students will gather on campus for a symposium in his honor. Seven scholars from across the U.S. — all of whom had Yarborough on their doctoral dissertation committees — will speak about their work while reflecting on Yarborough’s unique legacy.

In advance of the event, a UCLA colleague and two of his former students shared what Yarborough has meant to them personally, to their work and to the field that he has done so much to shape.

Kimberly Mack, an associate professor of English at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, will speak at the Dec. 6 symposium. She earned her doctorate from UCLA in 2015.

“His capacious idea of what Black writing is … is the reason I have the job I have and write the books I write.”

If it weren’t for Richard Yarborough, I would very likely not be in academia at all. His capacious idea of what Black writing is, how it works, and what it means for African American and American literary traditions, and American culture overall, is the reason I have the job I have and write the books I write.

His crucial work at the end of the 1980s as editor of the “Heath Anthology of American Literature” accomplished what it set out to do: It not only successfully expanded the American literary canon to include many deserving but long neglected BIPOC and white women writers, but it also highlighted the importance of music — songs (including blues lyrics!) and ballads — in the American literary tradition.

Richard would take this same multidisciplinary approach as he served as my dissertation chair. This was 2011, and I was convinced that I would have to keep my interests in creative writing and music criticism as separate (and quiet) as possible, lest I not be taken seriously as a budding scholar. I was shocked when Richard told me — completely out of the blue — that I shouldn’t feel like I have to be a rock critic over here and a lit scholar over there: “If you can find a way to bring music into your dissertation, and it’s intellectually sound, you can do it.”

I happily took him up on his suggestion, and I conceptualized a project that combined my interests in literature, popular music, and life writing. This research would eventually become a jumping off point for my first book.

I will be forever grateful to Richard for guiding me toward a more expansive and authentic vision for my academic work and life.

Yogita Goyal, like Yarborough, is a professor of English and of African American studies. She has been a member or the UCLA faculty since 2004.

“It would be an understatement to say that Richard’s career is actually the story of the African American literary tradition.”

In 2012, the American Studies Association announced a new annual award for scholars dedicated to excellence in mentoring, named after Richard A. Yarborough, who was also its inaugural recipient. It is rare enough for any scholar to earn such accolades, rarer still to also receive commendations from the City of Los Angeles and the County of Los Angeles. But Richard has deservedly been recognized at UCLA and beyond for his transformative impact on the study of African American literature and culture.

It would be an understatement to say that Richard’s career in the Department of English at UCLA is actually the story of the African American literary tradition and its development. At the moment of his arrival at UCLA in 1979, the study of 19th- and 20th-century African American literature continued to face immense challenges. Such difficulties included lost, damaged or neglected archives, an emphasis on canonical white writers to the exclusion of minority voices, and a focus on aesthetic questions that often bypassed the historical, cultural and political contexts that gave birth to African American literature.

Today, such approaches are no longer dominant, and African American literature at UCLA is an established and illustrious part of the curriculum. Richard’s efforts as a literary critic, historian, teacher, administrator and mentor have, in large part, been responsible for this transformation.

As a literary critic, Richard’s research on Reconstruction, violence, the American left, masculinity and the value of political fiction has proven to be powerful, prescient and enduring.

Whether thinking about Harriet Jacobs or Jimi Hendrix, Pauline Hopkins or Frederick Douglass, Black poetry and white patronage in 1890s Chicago, or violence, manhood and heroism in African American novels, Richard continues to inspire new generations of Americanist critics. He has thus built the field from the ground up, brick by brick, with finesse, elegance and generosity. Richard’s legacy will live on at UCLA and beyond.

Erin Aubry Kaplan, who earned her bachelor’s degree in English from UCLA in 1983 and an M.F.A. from UCLA in 1987, is a Los Angeles-based journalist.

“What was so revelatory was his compassion, the attention and respect he gave to naive but curious students.”

I was a junior, 1981 or ’82, when I first encountered Richard Yarborough in a seminar called Afro American Literature in the Nadir Period. I had no idea what this meant, but I was curious, about what the nadir period was (it turned out to be the decade before the turn of the 20th century, when lynchings in the South and racial terror in general was peaking) and about a course that was entirely about Black lit. That seemed almost too good to be true.

Up to that point the only Black literature I’d encountered in the major in two-plus years was Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” — one book in one survey course on American literature. And we spent only part of one class discussing it, which disappointed me because I came to class with so many questions. The white professor was game, but frankly at sea about the deeper meanings of the novel, and the mostly white students weren’t asking questions at all, so it kind of came and went. I was disappointed, but the urgent questions I had about that book stayed with me, refusing to go away.

In Richard’s seminar, those questions finally got a hearing. His class was a revelation, a window opening weekly into a world not just of literature but of history, politics, culture and personal meaning.

Richard’s reputation as a great (and very young) teacher preceded him, and he lived up to it. But what was so revelatory was his compassion, the attention and respect he gave to naive but curious students like myself who were looking to be more than just good students of Chaucer and Shakespeare; we were also striving to be ourselves at a university and in a department that didn’t exactly encourage it.

Richard broadened our knowledge immensely, but more importantly, he mentored us in the art of self-realization simply by showing us Black literature is every bit as emotionally resonant and complex and timeless as Chaucer and Shakespeare. It contains multitudes. This is the foundation he built and that I have been standing on for 35 years as a journalist. Words can’t thank him enough for that, and for being a friend.