Professor’s project creates 2nd ever book in endangered Philippine Indigenous language

Courtesy of Oona Paredes

Oona Paredes, photographed in the Philippines, hopes the book kicks off a longer-term effort to jumpstart a literary tradition for the Higaunon.

| August 11, 2025

“It may be the most important thing I will ever do in my life. Not just in my career, but as a human being.”

Oona Paredes, a UCLA associate professor of Asian languages and cultures, is referring to a project she completed recently that resulted in the second book ever published in the Higaunon language.

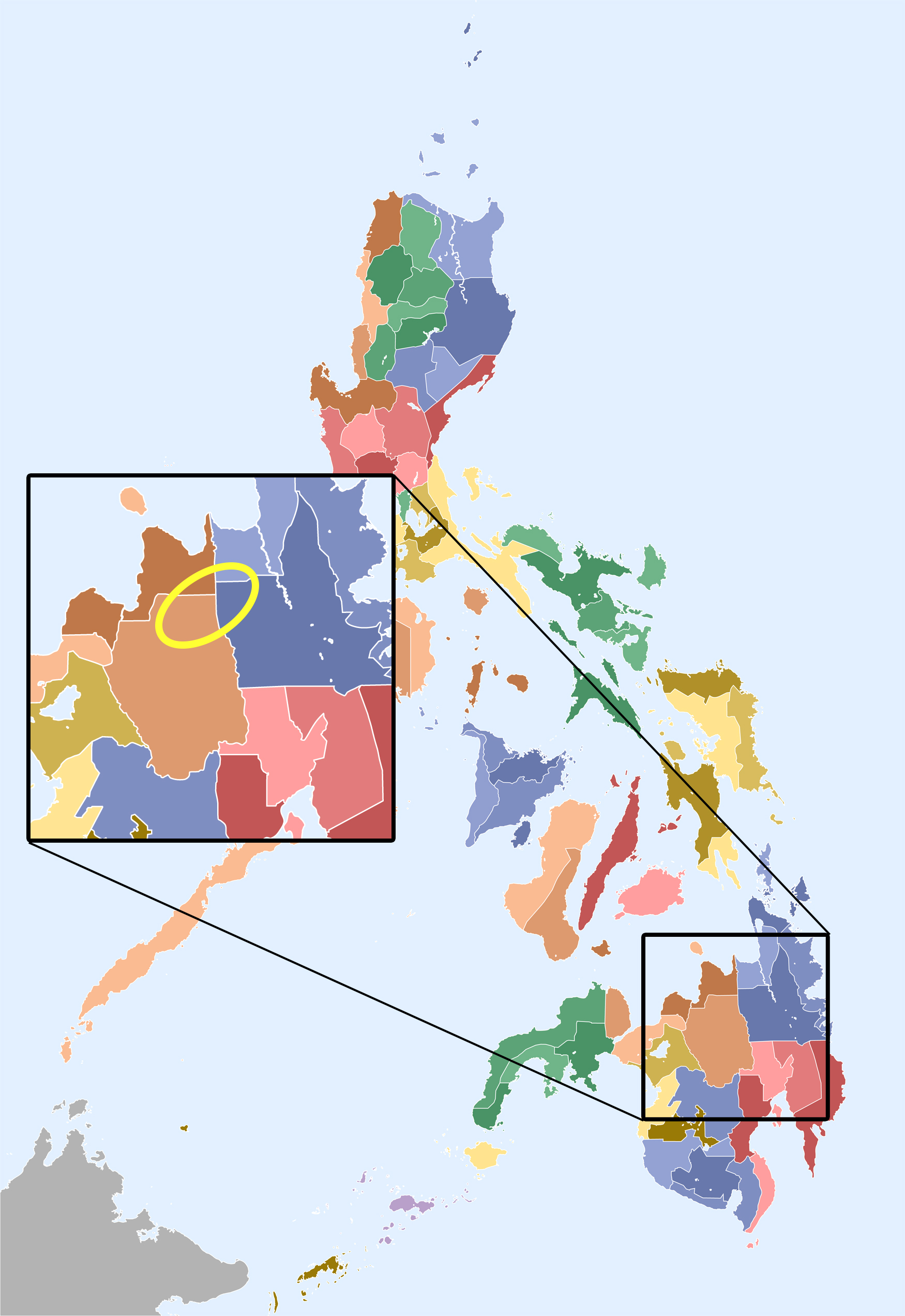

The Higaunon people, an Indigenous minority ethnic group in the Philippines, number roughly 250,000 and live in the mountains of north central Mindanao. For more than 200 years, they have maintained an oral tradition, with ancestral stories, laws and religious practices passed down across generations through spoken word. Until the late 20th century, their language had never been committed to paper.

The Higaunon people live in the mountains of north central Mindanao, roughly the area bounded by the yellow ellipse in the inset.

Then, in 1981, a Christian missionary group arrived in Higaunon territory and began working on the first-ever Higaunon orthography — a system for codifying a written language. That was a precursor to what became a 25-year-long effort to translate the New Testament into the Higaunon language.

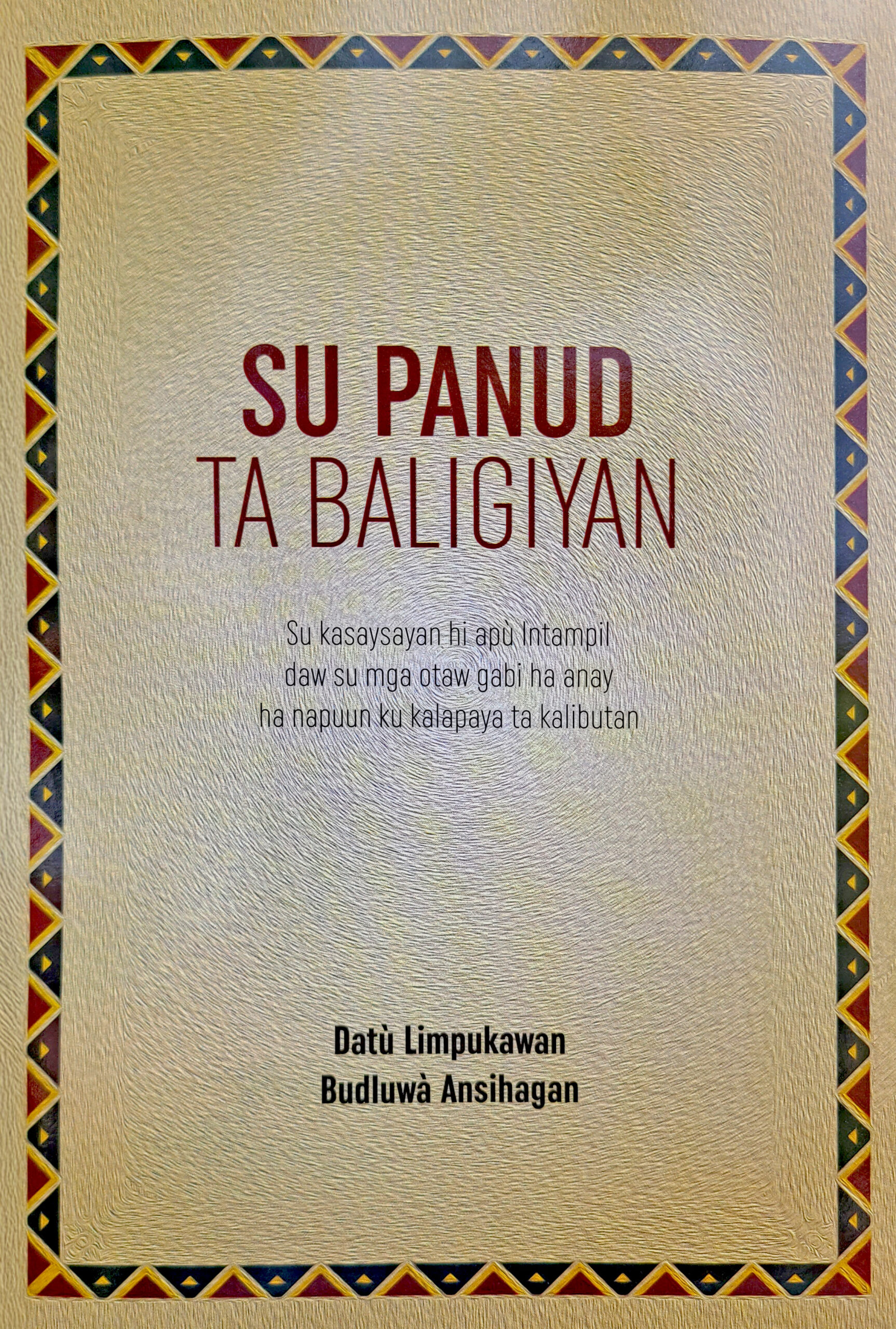

Years later, Paredes, who was raised in Mindanao, started a collaboration with members of a small Higaunon community called Baligiyan on what would become only the second book written in Higaunon — and the first centered on the Higaunon themselves. The project was as an offshoot of Paredes’s study of Indigenous political authority in the Philippines. As she was conducting preliminary research for that project, local leaders kept bringing up the Panud, a collection of the community’s foundational stories about its origins, history, religion and laws that have been passed down through the generations in chanted form.

“Three separate tribal councils told me that in order to answer the questions I was asking, you have to know the Panud,” she said.

A plan to preserve the language

When one datù, or community leader, Budluwà Ansihagan, agreed to teach Paredes about the Panud, he also expressed his concern that both the oral tradition and the Higaunon language itself were endangered. Together, they came up with a plan to write down the Panud.

If she had a thought about transcribing the stories herself, that idea faded within a few days. Initially, Paredes made audio recordings of datù Budluwà chanting the Panud and, with her limited Higaunon language skill, attempted to type the stories herself. “The next day, I would read my transcriptions back to them and they’d be rolling on the floor laughing,” she said.

So Paredes assembled a small team of community members to help. The work began in earnest in 2013, when Paredes was a professor at National University of Singapore. (She joined the UCLA faculty in 2019.) Although datù Budluwà, a man now in his 70s, was technically illiterate — like most of his contemporaries, he lacked formal schooling — it soon became clear that he had complete command of the stories in the Panud and an extraordinary memory. The datù would recite lengthy stories for the team to transcribe. When the book was nearing completion a decade later, the team read its work back to the datù, offering him the chance to make corrections.

Paredes (left) in conversation with the datù and her research assistant.

“There were times when we would read the first few words of a story he had told us, and he would pick it up from there, telling us the story in the exact same language he had used years earlier,” Paredes said. “We all followed along in amazement.”

Writing conventions for an oral tradition

The team didn’t need to invent an entirely new writing system for the Panud because they decided to use the orthography that the Christian missionaries had established years earlier. But Paredes said the team still debated basic writing conventions, like whether it was necessary to maintain consistent spelling throughout the book.

“They didn’t really understand why it mattered to spell words the same way each time, as long as they sounded the same when you read them out loud,” Paredes said. “That was a key lesson for me, because it helped me understand one of the fundamental differences between orality and literacy. I realized that, to them, this was still an oral tradition, and we were writing all of this down so that it could be read aloud.”

About 1,000 copies of the book were distributed to Baligiyan families and local schools.

The process also impressed upon her what might have been lost if nobody had thought to commit the stories to print: If not for the book, an entire trove of vital narratives would have been lost when the datù dies.

Apart from an interruption during the COVID-19 pandemic, Paredes returned to the region multiple times each year. She had a rudimentary knowledge of the language at the beginning of the project, but with each visit her understanding grew. By the end, she was knowledgeable enough to copyedit the final text.

Now, she is one of only a handful of people in North America who know the language.

Spreading the (written) word

When the manuscript was complete, 1,000 copies of the book were printed. The team distributed them to Baligiyan families and to nearby schools participating in a government-run education program for Indigenous peoples.

Then, Paredes and the team, along with a few other datùs, went on an impromptu book tour to several neighboring Higaunon communities.

“The team presented them with copies the book, told them how we did it, and encouraged them to write down their own traditions,” she said.

Paredes said she hopes the book is just the first phase of a longer-term project to jumpstart a literary tradition for the Higaunon. Already, a group of Higaunon college students is working on a translation into Cebuano Visayan, the local mainstream language, for wider distribution; that effort will enable Higaunons who never learned their mother tongue to access the Panud.

To complete the mission, Paredes would like to produce an annotated English translation, as a way to share the story of the Higaunon with the world. To Paredes, the existence of a written Panud is not just about cultural preservation, but also empowerment. “Everyone has the urge to understand where they came from,” she said. “But as marginalized minorities, having their heritage in tangible form as a book provides the Higaunon greater confidence to claim their place as equal citizens of their country.”