UCLA Library acquires new materials based on student proposals in English capstone course

Ben Alkaly/UCLA

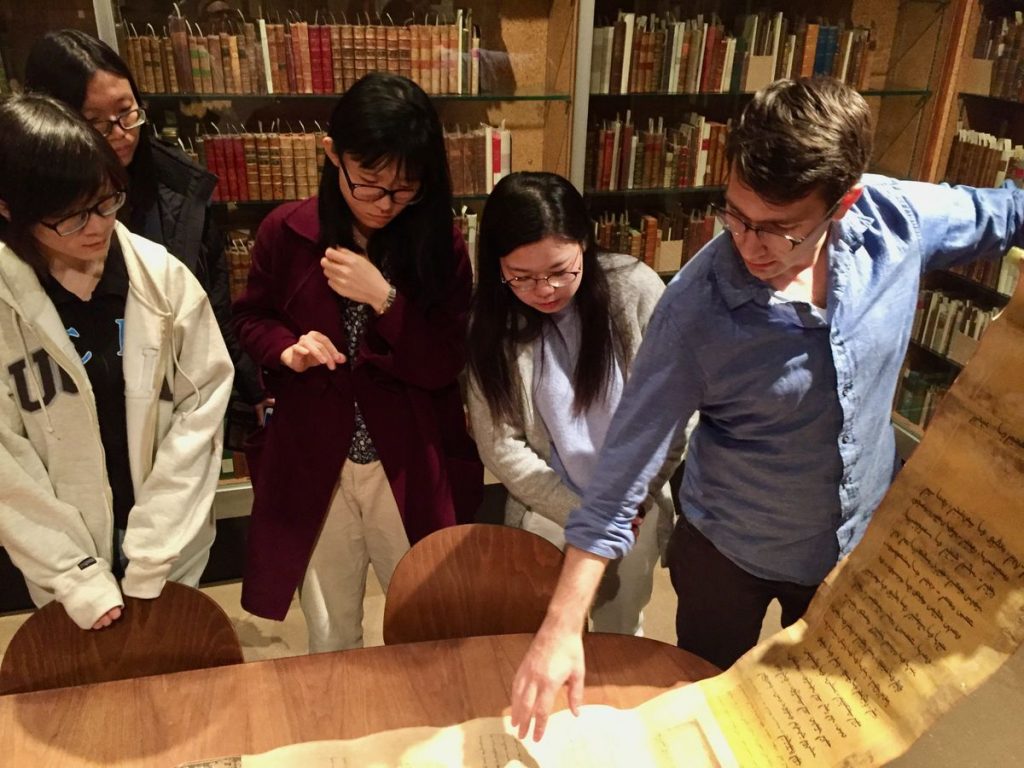

Devin Fitzgerald, shown here in 2018 working with students, helped create remote-learning alternatives during the pandemic for students to research, think and write about books and book collections in new ways.

| June 14, 2021

It’s been more than a year since the coronavirus halted physical access to the UCLA Library. Rather than seeing it as a hurdle, Matthew Fisher, associate professor of English, and Devin Fitzgerald, curator of rare books and the history of printing, devised a series of remote-learning alternatives for students to research, think and write about books and book collections in new ways, culminating in a final writing project that allowed students to explore an unfamiliar role: special collections curator.

The capstone course, “Writing the Digital Archive: Old Books in New Worlds,” was originally designed for students to work hands-on with manuscripts, rare printed books and archived primary source materials held in UCLA Library Special Collections. But with the shift to remote learning in 2020, Fisher and Fitzgerald collaborated to source digital materials instead.

“Students used digital surrogates to consider how special collections are assembled — and what’s excluded, how digital archives are curated and presented — and what voices are silenced, and how books are described, bought, and sold both physically and digitally,” said Fisher, who designed the capstone seminar for the English department and its new professional writing minor.

Fitzgerald met virtually with the students, inviting them into the world of collections curation by offering guidelines in researching materials for acquisition, interviewing book sellers, and in composing their final proposals.

“I described how curators consider collecting priorities, the current trends in UCLA collecting practices, and future directions,” Fitzgerald said.

Clarity Chua, a biochemistry and English major, said she was exposed to the concept of a book as an object in a detailed way for the first time in this course.

“I realized that it is not just the content of the book, or even just the historical context of a book which can contribute to its value,” Chua said, “but the materials of the book and unique quirks which make it special and distinct.”

While a variety of professional writing practices are emphasized in the course, from writing the descriptive and labeling text for museum displays and introductions to curated digital galleries, to critical and bibliographical essays, the final writing project had a bonus — the winning grant proposal and pitch would result in the acquisition of a new book or archive to be purchased by and added to UCLA Library’s distinctive collections.

At the end of the winter quarter, the special collections teaching committee read and discussed six grant proposals. They ended up purchasing not one, but recommendations made by two students, both of which will contribute to the library’s collection development goals relating to Latin American social and cultural history.

“In writing the acquisition proposal, I had to make a lot of historical, cultural and social connections while understanding the context of a specific item,” said Saori Borrayo, an English major and professional writing minor, who proposed the acquisition of three books about indigenous American languages: “Diccionario de Aztequismos” (1940), “Arte del Idioma Zapoteco” (1886), and “Arte de la Lengua Aymara” (1879).

“When I found the three books, I began to think about common links between them and how, in Latin America, there have been moments in history where indigeneity is commodified and exploited,” Borrayo said. “My research process stemmed from there; I continued to develop how these books on Indigenous literature both complicated and challenged academia’s role in settler colonialism.”

Chua’s pitch resulted in the library’s purchase of “Cruautés Horribles de Conquérants du Mexique,” written by Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, a mestizo whose father was Spanish, while his mother was a descendant of the Tetzcoco ruler Nezahualpilli, one of the last Aztec emperors, Cuitlahuac, as well as Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, who aided Hernan Cortés in his conquest of the Aztec.

“Some scholars consider Ixtlilxochitl controversial and revisionist in his writing of the history of Mexico and biased toward the Tetzcocan,” Chua said. “However, his account is particularly useful for modern scholars because he had access to the Tetzcocan oral history and it highlights the treatment of the Spanish to the royal descendants of their native allies.”

A second book, “Voyage Pittoresque dans Les Deux Amériques” edited by Alcide D’Orbigny, has two folding maps of the Americas, and was selected primarily as a companion book with a more Eurocentric viewpoint to compare and contrast with “Cruautés Horribles de Conquérants du Mexique,” she said.

Both students, having just graduated, are delighted that the books they proposed will soon be available for future generations.

“It’s been impactful to see how all my labor and dedication in that class has resulted in a plethora of knowledge on languages that can potentially serve current and future communities at UCLA and the greater Los Angeles area,” Borrayo said.