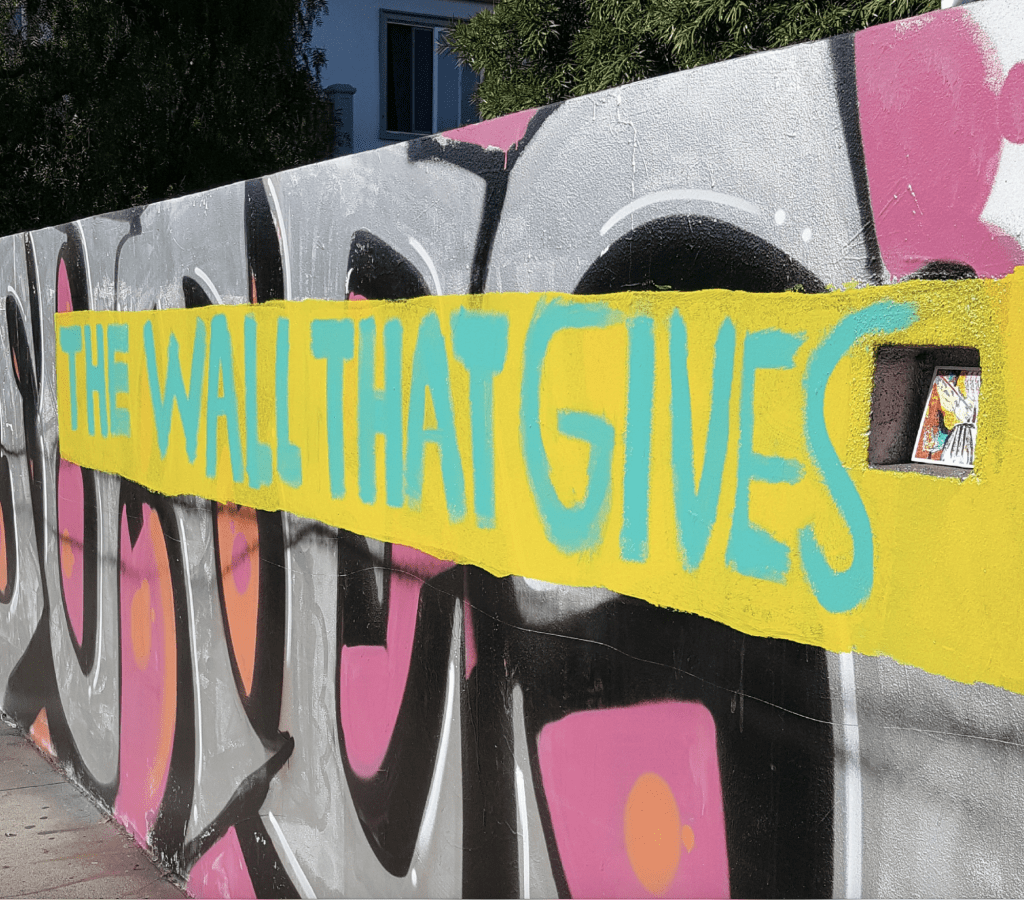

Professor Maite Zubiaurre explores generosity and political activism in “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da”

The Wall that Gives, an outdoor art installation by UCLA professor Maite Zubiaurre

| March 5, 2019

Walls are typically barriers that divide and separate us. For UCLA Germanic Languages and Spanish & Portuguese Professor Maite Zubiaurre, “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” is one way to encourage generosity amongst individuals and create a community that promotes reciprocity rather than exclusion, especially in today’s political climate.

Zubiaurre’s alter ego, Filomena Cruz, is a Venice, CA visual artist and trash-collagist. She was inspired to create this piece because “today’s world, and our current US government in particular, seem more keen than ever to create walls that separate and exclude. In reaction against hostile walls that take away, I decided to create a “Wall that Gives/El muro que da.”

There have been different iterations of “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” and Zubiaurre describes three of them in chronological order. She stresses that “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” does not happen in a void, but is yet another layer on a wall that became a communicative device from its inception and has a fascinating story to tell.

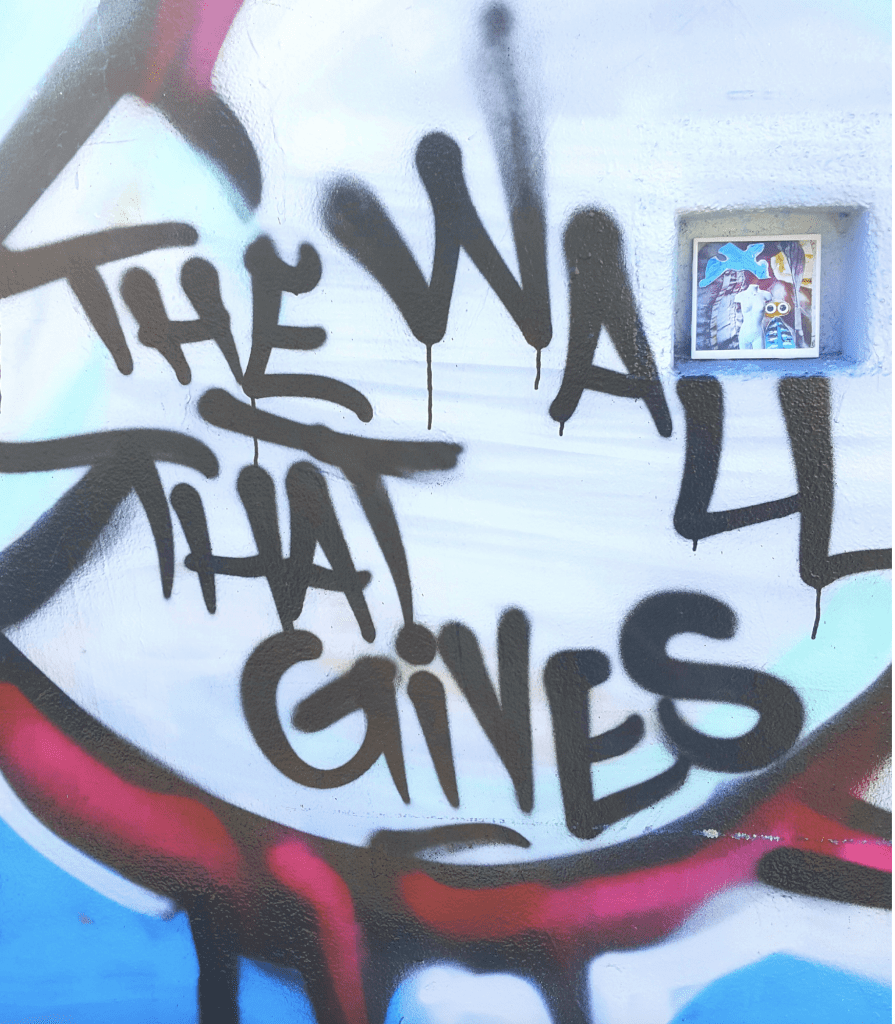

The “method” of “The Wall that gives/El muro que da” is very straightforward. Zubiaurre’s home in Venice, CA is separated from a busy avenue by a long wall. In 2015, she excavated a roughly 7×7 niche in the wall and vowed to leave a small art piece in it with (almost) daily regularity, free for grabs. The art pieces consist of 4×4 tiles on which she pastes reproductions of her “trashcollages” and then covers it with a coat of translucent, semi-gloss varnish.

When she bought the house in 2010, the wall was the canvas to an extensive mural, “Venice Rebirth Wall: A Mural dedicated to the People of Venice, CA,” by well-known Venice street artist and muralist Jules Muck. The mural never stayed “quiet.” The loud voices and colors of graffiti would continuously change its appearance, and sometimes leave an invasive imprint on cheeks and foreheads. Most of the time, however, graffiti would remain at the fringes and “politely” fill out the spaces between the faces.

One day, a neighbor woke Zubiaurre up with the shocking news that somebody had taken advantage of the dark of the night to savagely disfigure the faces of the mural by spraying thick, black swastikas on them. Police were called to the scene and she had no choice but to paint over the wall. For a while, its monotone grey served as a routine means of expression to graffiti artists or to “gang activity” (to use law enforcement jargon).

Interestingly enough though, graffiti diminished dramatically since she intervened the wall, and an altogether different “conversation” has started, and is still developing. Since then, artists have added their own drawings to the wall, and lately Zubiaurre has decided to “give” the wall to local muralists. The only requisite is that they integrate the words “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” into their art.

“The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” has now come full circle. As the article and short video on Zubiaurre’s wall and art by Melanie Camp, “Un muro que da and a Gang that took over” brings to the fore, Jules Muck, the muralist whose mural embellished the wall of her home when she bought it, is back, and is helping teenagers to overcome hardship via art. “But more importantly,” says Zubiaurre, “the generous impulse of the wall is now mirroring the spirit and generosity of a whole community. More often than not, when people take the tile, they leave something behind: a piece of fruit (I have found oranges, apples, grapes, bananas); a black T-shirt, carefully folded and tightly packed into the niche; a pocket magnifier staffed with a tiny reading lamp; a five-dollar bill under a stone “for somebody in need;” a cigarette pack with sprouting marijuana leaves; and, more recently, a dream catcher.”

Art-making and scholarly reflection combined have made Zubiaurre an activist. She feels that the “simple act of subverting the meaning of a wall, via art, and of substituting hostility with generosity has forced me to take a hard look at undocumented immigration and social injustice at the border.” Zubiaurre also plans on continuing with “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” as a “permanent” exhibit/community-generating artivist endeavor.

“The Wall That Gives/El muro que da” is a wall that brings people together rather than creating division. The local muralists who continuously change the wall spark conversation between individuals so that the wall (and the neighborhood) never stay quiet. By ensuring that artists integrate the words “The Wall that Gives/El muro que da” into their art, the wall’s message stands strong. It is more than just an art installation; every human interaction with the wall, whether it be taking a tile or creating a new mural, embodies the qualities of humanity, community, and generosity that neighbors need to feel for one another.