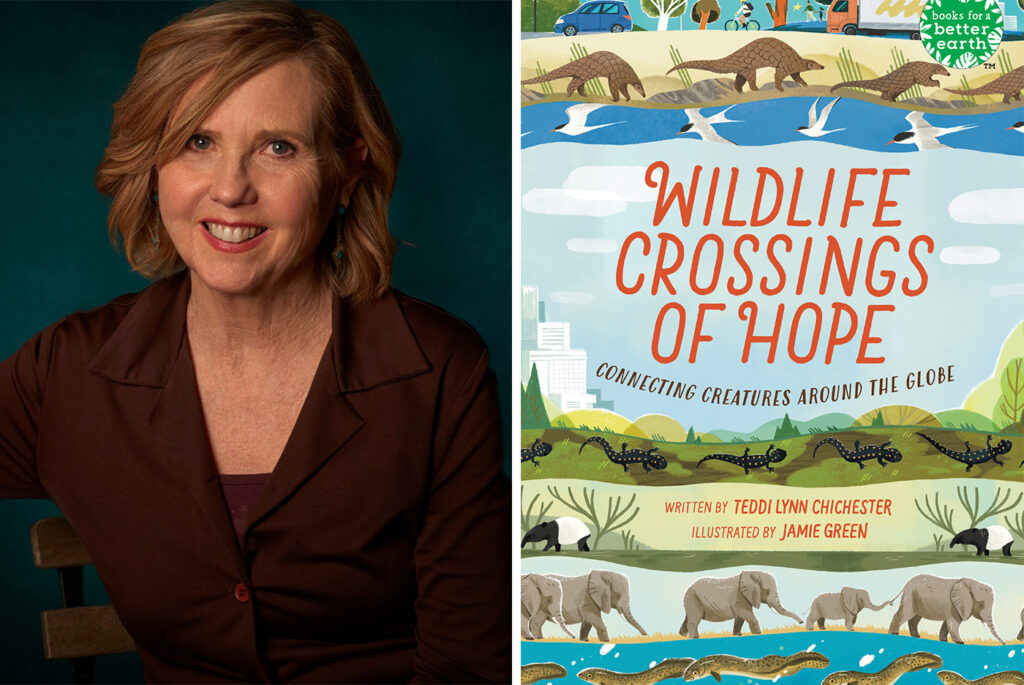

In her first book for young readers, Teddi Chichester aims to inspire compassion for wildlife

Daniel Sussman (portrait); Courtesy of Penguin Random House (book cover)

Teddi Chichester specializes in writing about the British Romantics; “Wildlife Crossings of Hope” is her first non-academic book.

| October 28, 2024

What happens to an ecosystem when wildlife can’t move freely due to colossal freeways and other human-made infrastructure? In her first book for young readers, UCLA Writing Programs lecturer Teddi Chichester sheds light on that complex problem.

“Wildlife Crossings of Hope: Connecting Creatures Around the Globe” (Holiday House) explores what happens to animals when they become trapped on shrinking patches of land called “habitat fragments.” If they attempt to traverse the roads or freeways that surround them, they risk getting killed by oncoming traffic. But staying within habitat fragments leads to inbreeding, ecological deterioration and, eventually, local extinction.

Through eight chapters, the book discusses the origins of the problem, some of the projects around the world that aim to create safer habitats for wildlife — including bridges over major roadways and other urban obstacles — and what the future might hold.

Chichester has taught at UCLA since 1992, and “Wildlife Crossings of Hope” is her first non-academic book; until now, most of her writing has been literary criticism of the works of 18th- and 19th-century British Romantics. Although the book might not immediately seem connected to her academic focus, Chichester said her scholarship was an inspiration for the new project.

“Poets of the British Romantic period helped me see most clearly just how magically the written word can conjure nature’s features … and creatures, and thus inspire us to love and want to protect them,” Chichester wrote on her website.

In an interview, Chichester said her writing process wasn’t altogether different from her previous work, either. “I did a lot of research for it just like with academic writing. But for this, I got to inject more of a personal voice through vignettes of my own experience.”

The book opens from Chichester’s point of view. Standing atop a mountain in Liberty Canyon, about 30 miles from her home, she recounts the story of the mountain lion known as P-22 as she surveys what will become the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing. The bridge, which will span the 101 Freeway, is expected to be completed in 2026, and it will be the largest wildlife corridor in the world.

Chichester visited the site frequently even before construction began. As she became increasingly familiar with the project, she got to know the bridge’s designer and started volunteering at the nursery whose native flora will later be planted on the bridge.

Plants and wildlife have been a lifelong passion for Chichester, thanks in part to her father, who was a botany professor and a California State Parks naturalist. Now, inspired by the massive wildlife crossing project, she decided that she wanted to motivate young people to take an interest in habitat preservation.

Chichester quickly realized that giving readers a full understanding of wildlife crossings — the book includes stories of 24 projects from 14 countries — would also require her to research and write about the problem of habitat fragmentation that prompted the construction of the bridges in the first place. The book also delves into the related challenges of restoring aquatic habitats by removing dams.

The book is geared toward middle school-aged readers, a group Chichester said is often caught in between the elementary storybooks meant for younger readers and young adult literature that can be too mature.

“I think middle schoolers, who are curious and emotionally open, are ready for challenging ideas and language, but still up for a good story,” she said.

While animals like P-22 have achieved celebrity status in recent years, particularly around Los Angeles, Chichester said the book intentionally spotlights species that tend to be less well known. She writes about white-lipped peccaries, western spadefoot toads, and weaver ants, all of which, she said, are vital to their ecosystems.

She hopes her book moves readers to take up the work of wildlife conservation and to carry with them the motto, “Make. Break. Don’t Take.” As in, make crossings and corridors, break down human-made dams, and don’t take any more remaining wildlife lands or the corridors that connect them. The book’s final call to action is “Stay curious, stay connected, and stay compassionate.” As Chichester writes, there’s a lot to be learned from these “marvelous creatures with whom we share this planet.”